The following is a roundup of some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and efforts to find treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the illness caused by the virus.

|

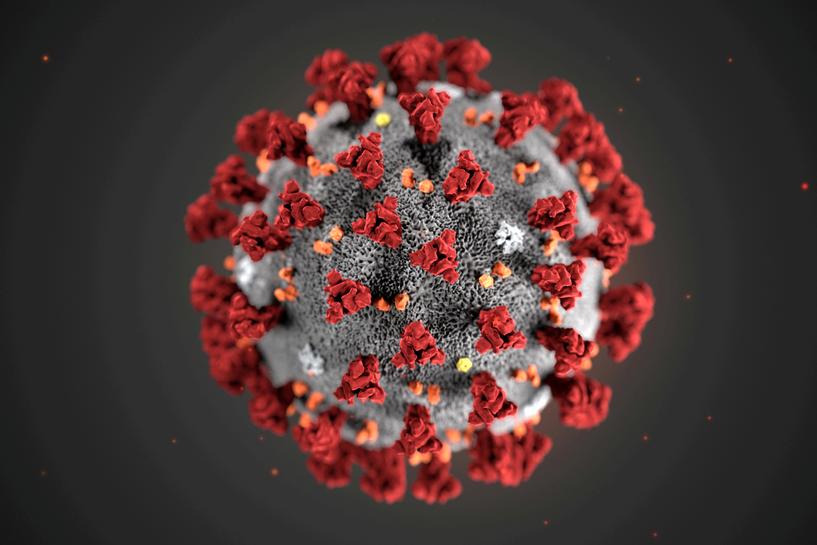

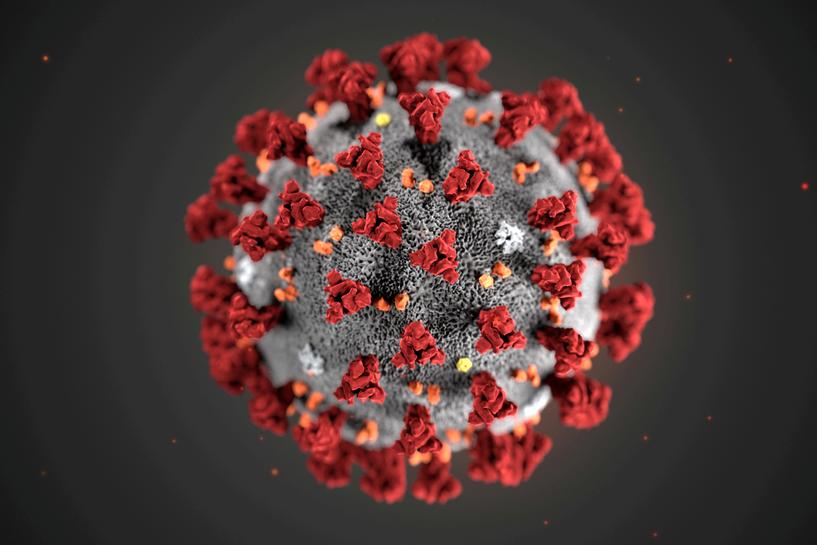

| FILE PHOTO: The ultrastructural morphology exhibited by the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV), is seen in an illustration released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. January 29, 2020. |

The following is a roundup of some of the latest scientific studies on the novel coronavirus and efforts to find treatments and vaccines for COVID-19, the illness caused by the virus.

Some common-cold antibodies might help fight COVID-19

Antibodies to the six coronaviruses that cause common colds cannot "neutralize" the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but antibodies to two of them might at least help the body fend off severe illness from the new virus, a small preliminary study suggests. German researchers studied 60 patients with COVID-19, including 25 who were hospitalized but not critically ill, 19 who required intensive care unit admission, and 25 who did not get sick enough to be hospitalized. The patients who needed intensive care all had significantly lower levels of antibodies to two seasonal coronaviruses, HCoV OC43 and HCoV HKU1, which the authors said are more closely related to the COVID-19 virus compared to the other human coronaviruses. While the observation does not prove these antibodies are responsible, "it is remarkable that the effect of HCoV OC43 and HKU1-specific antibody levels reached statistical significance regarding the need for intensive care therapy" in such a small study, the researchers said in a paper published on Tuesday in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases. "Further studies should validate this finding and explore the potential to identify persons at risk for severe disease course before a SARS-CoV-2 infection," they said.

Vaccine side effects may affect mammograms

Routine mammograms should be done either before the first dose of a COVID-19 vaccine or four-to-six weeks after the second dose, the Society for Breast Imaging advises. The vaccines' temporary side effects can include swollen lymph nodes around the armpits, which could be misread as a possible sign of breast cancer if it turns up on a mammogram. So-called axillary lymphadenopathy is usually seen in only 0.02%-0.04% of screening mammograms, according to the Society's guidelines. In trials of the Moderna vaccine, the condition developed in 11.6% of participants after the first dose and in 16% after the second dose. Researchers testing the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine did not routinely ask participants about armpit tenderness and lymph node swelling, but some people reported this side effect, which lasted an average of 10 days. More subtle effects on lymph nodes that are evident only on X-rays are likely to last longer, the Society said, although it is not clear yet what vaccination-related lymph node changes would look like. "As more information about the incidence and appearance of axillary lymphadenopathy following COVID-19 vaccination becomes available, it may be appropriate to change the duration of follow-up or final assessment recommendations," the Society said.

Nursing home staff lag in COVID-19 vaccinations

Residents of nursing homes are among the most vulnerable to severe COVID-19, but vaccinations appear to be lagging among staff members who care for them. By mid-January, roughly 714,000 U.S. nursing home residents and 582,000 staff members had received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine, U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) researchers estimated. When nursing homes were grouped by state, the average percentage of vaccinated residents ranged from 68% to 100%, while the average proportions of vaccinated staff ranged from only 19% to 67%, the CDC said. In a commentary published on Wednesday in JAMA, CDC researchers said that on average nationwide, no more than about one third of nursing home staffers had been vaccinated, which "is concerning because this population is at occupational risk for exposure to SARS-CoV-2." They said barriers to staff vaccination, including shift work schedules and lack of paid sick leave for vaccination side-effects, must be addressed. "Communication and outreach strategies are needed to improve vaccination coverage among this priority population," they said.

Celiac disease does not boost COVID-19 risks

Celiac disease does not increase patients' risk for infection or severe illness from the new coronavirus, new data show. People with celiac disease have defective immune activity and are known to be more vulnerable to a variety of viral infections, raising concerns they might also be more vulnerable to COVID-19. But when researchers used national databases in Sweden to compare 40,963 people with celiac disease to 183,892 similar people without it, they found no differences in risks of infection, COVID-19 related hospitalization, critical illness requiring intensive care, or death from the disease. In a report published on Thursday in Clinical Epidemiology, the authors note that Sweden has imposed only limited social distancing regulations, and "the lack of a generalized lockdown is likely to have increased the number of individuals exposed to COVID-19." In this setting, they report, the risk of hospitalization for COVID-19 was about 1-in-1000 and the risk of being diagnosed with COVID-19 was about 1%. "There was no difference in these outcomes when comparing celiac disease patients to controls."

(Source: Reuters)