A microorganism scooped up in deep-sea mud off Japan's coast has helped scientists unlock the mystery of one of the watershed evolutionary events for life on Earth: the transition from the simple cells that first colonized the planet to complex cellular life - fungi, plants and animals including people.

|

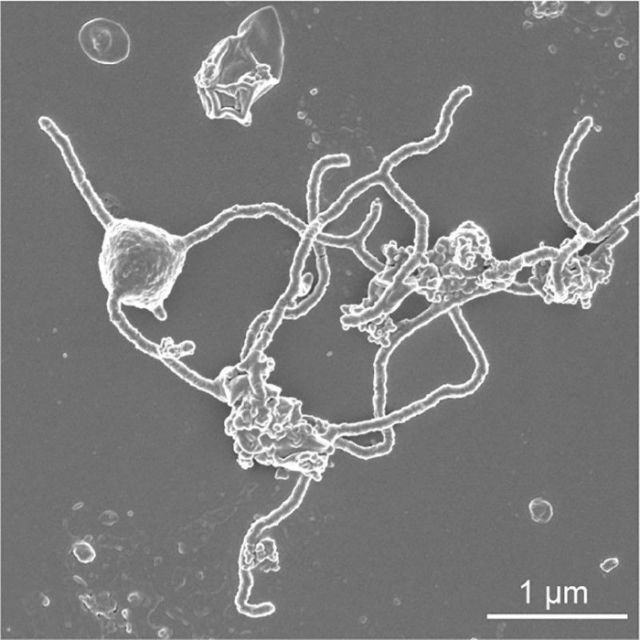

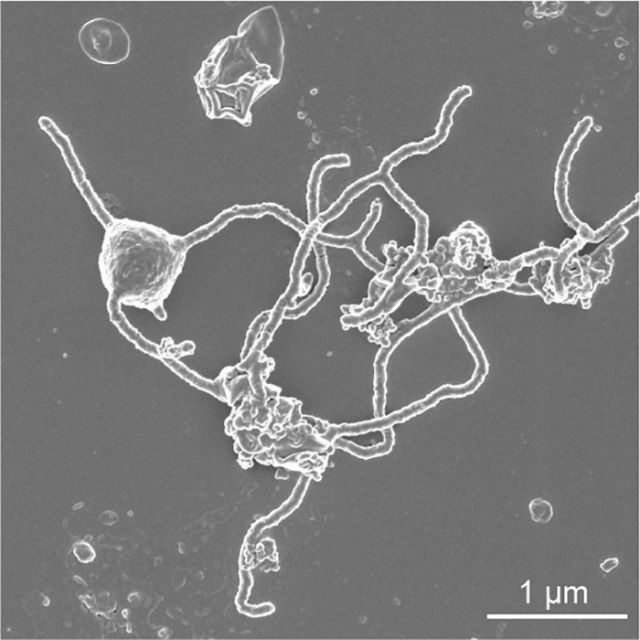

| A scanning electron microscopy image of the single-celled organism Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum strain MK-D1 showing the cell with tentacle-like branching protrusions is seen in this image released at the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology (JAMSTEC) in Yokosuka, Japan on January 15, 2020. |

A microorganism scooped up in deep-sea mud off Japan’s coast has helped scientists unlock the mystery of one of the watershed evolutionary events for life on Earth: the transition from the simple cells that first colonized the planet to complex cellular life - fungi, plants and animals including people.

Researchers said on Wednesday they were able to study the biology of the microorganism, retrieved from depths of about 1.5 miles (2.5 km), after coaxing it to grow in the laboratory. They named it Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, referring to the Greek mythological figure Prometheus who created humankind from clay and stole fire from the gods.

Prometheoarchaeum’s spherical cell - with a diameter of roughly 500 nanometers, or one-20,000th of a centimeter - boasts long, often branching tentacle-like appendages on its outer surface.

It is part of a group called Archaea, relatively simple single-cell organisms lacking internal structures such as a nucleus. Scientists have long puzzled over the evolutionary shift from such simple bacteria-like cells to the first rudimentary fungi, plants and animals - a group called eukaryotes - perhaps 2 billion years ago.

Based on a painstaking laboratory study of Prometheoarchaeum and observations of its symbiotic - mutually beneficial - relationship with a companion bacterium, the researchers offered an explanation.

They proposed that appendages like those of Prometheoarchaeum entangled a passing bacterium, which was then engulfed and eventually evolved into an organelle - internal structure - called a mitochondrion that is the powerhouse of a cell and crucial for respiration and energy production.

The solar system including Earth formed 4.5 billion years ago. The first life on Earth, simple marine microbes, appeared roughly 4 billion years ago. The later advent of eukaryotes set in motion evolutionary paths that led to a riotous assemblage of organisms over the eons like palm trees, blue whales, T. rex, hummingbirds, clownfish, shiitake mushrooms, lobsters, daisies, woolly mammoths and Marilyn Monroe.

“How we - as eukaryotes - originated is a fundamental question related to how we - as humans - came to be,” said microbiologist Masaru Nobu of Japan’s National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, one of the leaders of the study published in the journal Nature.

Prometheoarchaeum is a member of a subgroup called Asgard archaea - named for the dwelling place of the gods in Norse mythology. Other members of this subgroup were retrieved from the frigid seabed near a hydrothermal vent system called Loki’s Castle, named after a Norse mythological figure, between Greenland and Norway.

The research on Prometheoarchaeum, Nobu said, indicates that the Asgard archaea are the closest living relatives to the first eukaryotes.

The researchers used a submersible research vessel to collect mud containing Prometheoarchaeum from the Omine Ridge off Japan in 2006. They studied it in the laboratory in a years-long process and watched it slowly proliferate after incubating the samples in a vessel infused with methane gas to simulate the deep-sea marine sediment environment in which it resides.

“We were able to obtain the first complete genome of this group of archaea and conclusively show that these archaea possess many genes that had been thought to be only found in eukaryotes,” Nobu said.

Prometheoarchaeum was found to be reliant on its companion bacterium.

“The organism ‘eats’ amino acids through symbiosis with a partner,” Nobu said. “This is because the organism can neither fully digest amino acids by itself, gain energy if any byproducts have accumulated, nor build its own cell without external help.”

(Source: Reuters)