Scientists are developing dust-sized wireless sensors implanted inside the body to track neural activity in real-time, offering a potential new way to monitor or treat a range of conditions including epilepsy and control next-generation prosthetics.

|

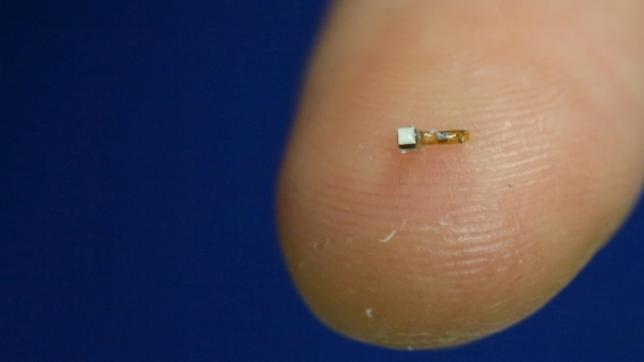

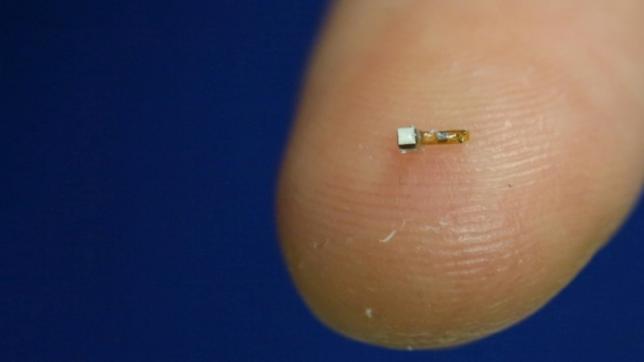

| A dust-sized wireless sensor that makes it possible to wirelessly monitor neural activity in real time when implanted inside the body, is shown on a finger in this handout photo. |

Scientists are developing dust-sized wireless sensors implanted inside the body to track neural activity in real-time, offering a potential new way to monitor or treat a range of conditions including epilepsy and control next-generation prosthetics.

The tiny devices have been demonstrated successfully in rats, and could be tested in people within two years, the researchers said.

"You can almost think of it as sort of an internal, deep-tissue Fitbit, where you would be collecting a lot of data that today we think of as hard to access," said Michel Maharbiz, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at the University of California, Berkeley.

Fitbit Inc sells wearable fitness devices that measure data including heart rate, quality of sleep, number of steps walked and stairs climbed, and more.

Current medical technologies employ a range of wired electrodes attached to different parts of the body to monitor and treat conditions ranging from heart arrhythmia to epilepsy. The idea here, according to Maharbiz, is to make those technologies wireless.

The new sensors have no need for wires or batteries. They use ultrasound waves both for power and to retrieve data from the nervous system.

The sensors, which the scientists called "motes," are about the size of a grain of sand. The scientists used them to monitor in real time the rat peripheral nervous system - the part of the body's nervous system that lies outside the brain and spinal cord, according to findings published last month in the journal Neuron.

The sensors consist of components called piezoelectric crystals that convert ultrasound waves into electricity that powers tiny transistors in contact with nerve cells in the body. The transistors record neural activity and, using the same ultrasound wave signal, send the data outside the body to a receiver.

The researchers said such wireless sensors potentially could give human amputees or quadriplegics a more efficient means of controlling future prosthetic devices.

"It's a meaningful advancement in recording data from inside the body," said Dr. Eric Leuthardt, a professor of neurosurgery at Washington University in St. Louis. "Demonstrations of capability are one thing, but making something for clinical use, to be used as a medical device, is still going to have to be worked out."

Before implanting wireless sensors into the brain, the science of understanding how the brain processes and shares information needs to advance further, Leuthardt said.

To deliver motes, currently one millimeter in size, into the brain, the researchers would need to miniaturize the sensors further to about 50 microns, about the width of a human hair.

(Source: Reuters)