Scientists on Thursday announced the creation of a synthetic organism stripped down to the bare essentials with the fewest genes needed to survive and multiply, a feat at the microscopic level that may provide big insights on the very nature of life.

|

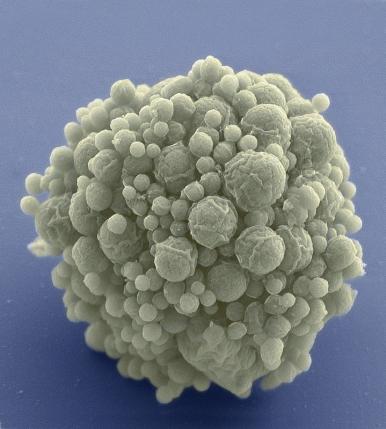

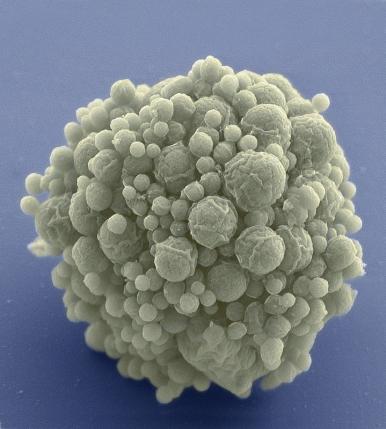

| Electron micrograph image shows synthetic cell clusters of JCVI-syn3.0 cells magnified at about 15,000 times in this image released on March 24, 2016. |

Scientists on Thursday announced the creation of a synthetic organism stripped down to the bare essentials with the fewest genes needed to survive and multiply, a feat at the microscopic level that may provide big insights on the very nature of life.

Genome research pioneer J. Craig Venter called the bacterial cell his research team designed and constructed the "most simple of all organisms." While the human genome possesses more than 20,000 genes, the new organism gets by with only 473.

"This study is definitely trying to understand a minimal basis of life," said Venter. But the researchers said that even with such a simple organism, that understanding remained elusive.

They noted that even though their organism has so few genes, they were still uncertain about the function of nearly a third of them, even after more than five years of work.

The researchers predicted their work would yield practical applications in developing new medicines, biochemicals, biofuels and in agriculture.

"Our long-term vision has been to design and build synthetic organisms on demand where you can add in specific functions and predict what the outcome is going to be," said Daniel Gibson, vice president for DNA technologies at Synthetic Genomics Inc, the company handling commercial applications from the research.

"I think it's the start of a new era," Venter added.

Venter helped map the human genome in 2001 and created the first synthetic cell in 2010 with the same team that conducted the new research.

That 2010 achievement, creating a bacterial organism with a manmade genome, demonstrated that genomes can be designed on a computer, made in a laboratory and transplanted into a cell to form a new, self-replicating organism.

Having created that synthetic cell, the researchers set out to engineer a bacterium by removing unessential genes. The goal was to use the fewest genes necessary for the organism to live and reproduce.

Venter said initially "every one of our designs failed" because they took out too many genes, and had to restore some.

Orchestra, not piccolo player

Venter said one lesson was that to understand life, it is more important to look across the entirely of a genome, an organism's complete genetic blueprint, rather than at individual genes.

"Life is much more like a symphony orchestra than a piccolo player. And we're applying the same philosophy now to our analysis of the human genome, where we're finding most human conditions are affected by variations across the entire genome" rather than a single gene, Venter said.

The researchers said they created a minimal cell possessing the smallest genome of any self-replicating organism. They said a cell with even fewer genes could be possible although it might, for example, reproduce excruciatingly slowly.

Microbiologist Clyde Hutchison of the J. Craig Venter Institute in La Jolla California, lead author of the study in the journal Science, said the goal is to figure out the functions of all the cell's genes and make a computer model to predict how it would grow and change in different environments or with additional genes.

"It's important to realize there is no cell that exists where we know the functions of all the genes," Hutchison said.

The environmental group Friends of the Earth expressed concern about the research, citing the lack of government regulations specific to synthetic biology and gene editing technologies.

"Living organisms like bacteria are not machines to be rewired," said Dana Perls, an official of the group. "Not even the scientists know the biological function of 149 of these genes, which raises safety concerns. If we don't fully understand the science, it is more difficult to manage biosafety concerns."

The research might shed light on the origins of life on Earth billions of years ago. "We may be getting hints of some early fundamental mechanisms that coincide with some of the most primitive kind of life forms," Venter said.

"I think as we get the ability to explore further in the universe, my view is wherever we have the same chemical constituents, which is almost everywhere, life will happen," Venter said. "But that's a philosophical point until it's proven."

(Source: Reuters)